http://www.abc.net.au/foreign/content/2009/s2631046.htm

300 多年前, 在 Northern Ireland, 大概有一大部份人是來自Ireland, 他們相信 Catholicism. 而剩下的另一大部份人是來自Scotland & England, 他們相信Protestantism 新教教會(應是Anglicans, 請看以下解說). 於是他們互相憎恨, 當然Catholics 都想趕走那些Protestants, 咁 Ireland 就可統一了, 但是 Northern Ireland 是英國領土, 英政府說Protestant 住了那麼久, 點可搬走他們呢. 於是為了平亂, 便建了一圍牆分隔兩教住民了.

{ Protestant 原自 Catholics (當然, Catholics 也是原自 Christians), 自 Martin Luther (1483-1546 德國人)從天主教教庭分列出來後. 便自立門戶來反對羅馬教宗而成立了Protestantism. 在英國的 Henry the Eight (1491-1547)睇到 Martin Luther 的成功, 為了廢除現在皇后, 娶個女侍官. 於是佢又要出來反對羅馬教庭而成立了 Anglicans 聖公會(因為他們也是反對天主教的POPE, 所以都叫Protestant). Henry the eight, 成立了聖公會後, 斬鬼咗個第二個老婆個頭, 前前後後共娶了6位老婆!!!!} 0依!!! 睇嚟做男人, 信聖公教會好過天主教囉, 可以不斷換老婆!!!! 哈哈哈!!!!

Kilometres of high concrete walls snake through Belfast in Northern Ireland - graffiti daubed and grim. They divide catholic neighbourhoods from Protestant.

They’re called the Peace Walls.

But do they keep the enduring hatred and suspicion locked outside or inside?

The consensus among the locals participating in this story is pretty clear – if the walls came down there would be a swift return to the bad old days of intractable sectarian violence.

'If you pull that wall down there’ll be murder, mayhem, there’ll be blood spilt, you can guarantee now, there’ll be big, big trouble.'

William Brown, loyalist resident.

Even as Europe Correspondent Phil Williams was putting the final touches to his story on the quality of peace in Northern Ireland, he found himself in the middle of a dangerous melee. Petrol bombs and water cannon exploded as police tried to break up a riot that had erupted around one of the traditional annual Orange Day parades.

It was a frightening example of what happens when Catholic and protestant communities chafe, undivided by the so-called peace walls.

“Well it’s ugly, it’s horrible, but at the minute, it’s necessary. But there’s also walls of prejudice … walls that were built 300 years ago here and they're still here in legislation, in prejudice and bigotry. So those are the walls that are going to have to come down first.” Sean McVeigh, Republican resident

Despite marked political progress since the signing of the 1998 Peace Agreement, steps towards mending the enduring divisions between some Catholic and Protestant communities have been much slower.

In recent months the killing of two soldiers, a policeman and a Catholic community worker indicate that the tensions of The Troubles still lurk very close to the surface.

Are the Peace Walls monuments to the past or vital and necessary peace-keepers in the present and the future?

_________________________________Transcript

WILLIAMS: Like veins they snake through the city streets, across parks, through schools. Twenty kilometres of suspicion and hatred separated by bricks, metal and wire. But as well as providing protection from the rocks, bottles and pipe bombs, the so-called ‘peace walls’ also offer opportunity, employment and a sense of purpose.

China has its Great Wall – Berlin used to have one and now no visit here is complete without a tour of the mighty walls of Belfast.

SEAMUS KELLY: We’re now in Comway Street and I remember this particular street in 1969 as a 16 year old. I remember the gunfire coming from the Shankill, which is only fifty metres ahead of us here. You can actually see the dividing peace wall and I just remember running, jumping into the houses to get down out onto the safety of the Falls Road at that particular time. Quite an experience.

WILLIAMS: In his wildest dreams Seamus Kelly could not have foreseen that he would end up as a tour guide, explaining the troubles from a Nationalist point of view and how he and so many of his friends ended up in prison after fighting for a united Ireland.

SEAMUS KELLY: [Republican tour guide] “It’s emotional, but there’s been much more things that have happened since then, between then and now that have been much more emotional. When I relate to the H blocks and the hunger strikes and the comrades who I knew, spent time with, who actually died on hunger strike - that to me is very, very emotional. That’s raw, that’s like yesterday, although it’s twenty-eight years ago. That’s very, very raw.

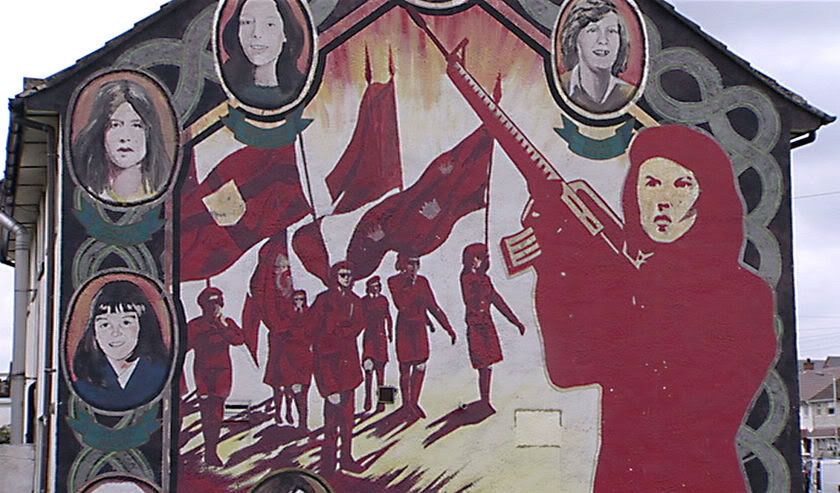

WILLIAMS: The tour takes in the murals and the memorials to the fallen and provides jobs for former IRA prisoners like Seamus Kelly.

“You wouldn’t consider going through these gates yourself and doing the tour on the other side?”

SEAMUS KELLY: “It wouldn’t be practical. I wouldn’t be talking about a…. ah coming from a unionist perspective, so that’s why loyalist ex prisoners would do that”.

WILLIAMS: [Handover to other tour guide on other side of the wall] Through these gates it’s loyalist territory and time for a change of guide and side.

“Twenty years ago you’d have been trying to kill each other”.

SEAMUS KELLY: “That’s correct, but times move on. There’s a whole new political dispensation here in Ireland at the moment. Projects such as this help… that understanding”.

WILLIAMS: Neither side has changed fundamental beliefs but the days of assassinations and knee cappings appear to be over.

WILLIAM SMITH: “It’s like the fear of being killed, it’s like the fear of being blown up…”.

WILLIAMS: Loyalist tour guide, William Smith, also spent time in prison during the troubles. The transformation from war zone to tourist town was unimaginable a few years ago.

WILLIAM SMITH: [Loyalist tour guide] “I was in prison for attempted murder, but I mean that may sound… you know really, what would you call it, bizarre now at this particular time, but in that, in 1970, thousands of young men went to prison. I will always say that that was a lost generation”.

WILLIAMS: At least some in that generation are now finding a new sense of purpose, explaining their side of the conflict to visitors who’ve left thousands of messages on the walls.

WILLIAM SMITH: “Tourists from all over the world will come here and they will write a message”.

WILLIAMS: “I can see one here from Sara Nicolas from Australia”.

WILLIAM SMITH: “Oh yeah, yeah there’s plenty of Aussies”.

WILLIAMS: While we walk the wall, more tourists draw their conclusions on it. Here the writing on the wall is almost exclusively from foreigners.

TOURIST: “I think it is kind of an odd thing, I think it would make more sense to see locals coming to sign the wall instead, so….. and that would make it a peace wall for sure”.

WILLIAMS: It’s an extraordinary transformation when tourism supplants terrorism. This is enormous progress but while the visitors come and go, the walls remain, splitting two communities.

“It may seem strange that years after the Good Friday Agreement was signed, although there was political progress and measurable, as chaotic as it may sometimes be, here at the interface where Catholic meets Protestant these walls are still as they were. In fact there have been more built because the people here see them not as dividing communities but protecting them”.

And this is what can happen where there are no walls. In the north Belfast area of Ardoyne there’s been a tradition of violence handed down from one poisoned generation to another. It erupted again during the annual Orange Order marches. Hopes had been so high that this was over - and the day begun so differently.

NELSON MCCAUSLAND: [Culture Minister, Northern Ireland] “Well the 12th of July is a special occasion, it’s one of the most important dates for me in the year. As you can see it’s a great carnival, a great festival. You’ve only to look at the parade itself and see the artistry of the banners, the music of the bands, the colour of the occasion, the great crowds that are out. It’s a family occasion. You’ve grandparents, parents and children. It’s a day really that could be enjoyed by anyone”.

WILLIAMS: You won’t see many Catholics here. Most see this celebration of the Protestant victory at the battle of the Boyne in 1690 as offensive and a provocation. The majority stay away, but four years of relative peace came to a violent end this time.

[On street] “You can see things are getting very tense here. The marchers are expected to come up through this area, a Catholic area very soon and there’s a large police presence trying to hold the Catholic protestors back. This is just an expression of the sort of tension this day evokes and at the moment, it’s getting very rough”.

The Ardoyne has long been a flashpoint. It’s where Catholic and Protestant territories meet. No wall keeping them apart. No place either for an Orange order march according to these people. Everyone here is used to the rocks and even the petrol bombs - and in reply, the baton rounds and the water canon. But for the first time since the 1970’s, someone fired a gun here - a worrying new threat that had police on edge.

Eventually the Orange Order did pass as the rocks and abuse rained down on them. Sinn Fein’s, Gerry Kelly was quickly on the scene, blaming the Orange Order for marching here, but also dissident Republican groups like the Real IRA for organising the attacks.

“What does this say about the peace process?”

GERRY KELLY: [Sinn Fein MLA] “The peace process is solid, the political process is solid, let us not exaggerate what happened here. These are small micro groups who incidentally came together when they thought they saw the opportunity to bring down the peace process. In a single incident, in a single night they will not achieve that. They will feel…. they have already felt…... They have no strategy… they are going nowhere”.

MARTIN MCGUINNESS: [Deputy First Minister, Northern Ireland] “It’s very important not to, and it’s even important for the Australian Broadcast Media not to distort what happened over the last couple of days from the overall picture which has I think been a very good news story world wide for some fifteen years”.

(News reports of the killing of two soldiers)

WILLIAMS: It’s an optimism not reinforced by recent events, a series of killings over the last few months. The first left two soldiers dead - shot at an army post - and two days later, the Dissident Continuity IRA was blamed for the murder of Constable Stephen Carroll – the first policeman killed in a terrorist attack in Northern Ireland for twelve years.

KATE CARROLL: “He was my life - my son and my husband were my life and I just feel now that I’m dead inside”.

WILLIAMS: Another funeral, this time forty nine year old Catholic community worker Kevin McDaid. He was beaten to death as he tried to help a friend being attacked by a mob. His wife was bashed too. Amongst the mourners was Deputy First Minister Martin McGuinness.

MARTIN MCGUINNESS: “We have to see all of this in a proper perspective. The big story of the killings over the last number of weeks has been the way in which the political process has come together to repudiate the activities of those who would try to plunge us back into the past. You cannot compare, under any circumstances, the way things are today from where they were fifteen or twenty years ago. We are in a fundamentally different and better place”.

WILLIAMS: It is true despite the recent setbacks, it’s still a long way from the bad days of open sectarian warfare and ironically the very structures that divide, also secure.

WILLIAM BROWN: “In a perfect world it would be great to see peace but let’s face it, it’s Belfast, Northern Ireland - and there’s never going to be peace here”.

WILLIAMS: Loyalist William Brown and his family have lived for years across the road from one of the walls. Talk of knocking them down is not seen here even as a faint possibility.

MRS BROWN: “No, definitely not. For everyone’s sake it’s best just to keep the wall up, to keep the peace”.

WILLIAM BROWN: “Aye if you pull that wall down, there’ll be murder, mayhem, there’ll be blood spilt. You can guarantee now, there’ll be big, big trouble”.

WILLIAMS: “So we’re just coming on dark now, is this about when the rioting would start when you were young?”

WILLIAM BROWN: “Yes when the night falls and the rain falls, that’s when we’d come out”.

WILLIAMS: William Brown takes me the few hundred metres from his house to the same place where the political tours do their handovers.

WILLIAM BROWN: “I don’t trust anyone. I wouldn’t trust anyone with my life”.

WILLIAMS: “No chances of peace?”

WILLIAM BROWN: “There’s no peace here and there’ll never be peace”.

WILLIAMS: “That’s a pretty pessimistic view isn’t it?”

WILLIAM BROWN: “Well I’m the one living on the peace line. I know, I’ve seen it. You will always have your factions. This place is like, like the Palestinians and the Israelis – this is the same scenario”.

WILLIAMS: On the Republican side, Sean McVeigh cannot escape the shadow of the walls. He lives too close to forget this has been a war zone and his family and home attacked.

“How do you feel about this wall now? Would you like to see it down?”

SEAN MCVEIGH: “Well it’s ugly, it’s horrible but at the moment it’s necessary. You know it’s, in my mind, walls aren’t only physical, aren’t only made of mortar or steel or wire, but there’s also walls of prejudice. There’s walls that were built 300 years ago here and they’re still here in legislation and the prejudice and bigotry so those are the walls that are going to have to come down first”.

WILLIAMS: It’s a sentiment echoed across this city – it’s attitudes, not masonry that need dismantling…. and Father Aiden Troy has learned from bitter experience.

FATHER TROY: [2001 footage] “I was terrified, but I was terrified not for myself so much but I was terrified some child was going to be killed or very badly injured - and with that a live device, a bomb was thrown over. In that split second it dawned on me, this is beyond anything that anyone could have imagined”.

WILLIAMS: Back in 2001, Father Troy found himself in the middle of one of the ugliest confrontations in recent years as Protestants tried to stop Catholic children from walking through their area on their way to school.

FATHER TROY: “We were always very conscious that once we got through the gate they moved without looking left or right, right into the school”.

WILLIAMS: “Now that terrible period is over but the conflict isn’t over is it?”

FATHER TROY: “No I think this is one of the very sort of worrying aspects that I think I’ve learnt so much from this. I this peace is very much a gradual process and I think there is genuinely a move forward but there’s always the danger of slipping back”.

WILLIAMS: There are no riots here. At Hazelwood Integrated Primary in North Belfast, Catholics and Protestants share the playground, and the classroom. The main lesson here is if you educate people together, you can break the cycle of distrust.

PEACHES MCCORRY: “If it was a Catholic school only Catholics could go there”.

WILLIAMS: “And what do you think about that?”

PEACHES MCCORRY: “I don’t know”.

WILLIAMS: “Do you think that’s a good idea or not?”

PEACHES MCCORRY: “I don’t think it is because it’s good to let other people in your school”.

WILLIAMS: “Do you think about if they’re a Catholic or a Protestant?”

FEMALE STUDENT: “No, it doesn’t really matter”.

WILLIAMS: Despite the obvious success here, few of Northern Ireland schools are integrated and for Principal Jill Houston, it’s been a frustrating struggle against entrenched opposition.

JILL HOUSTON: [Principal Hazelwood Integrated Primary] “Opposition from government, opposition from parents, opposition from churches but a total belief that having children educated together is sensible. It shouldn’t be something that’s different. It should be the total norm in any normal society”.

WILLIAMS: “And yet there’s only about five per cent of Northern Ireland children in schools like this.”

JILL HOUSTON: “Yes. Basically I regret to say our politicians and our senior civil servants and our people who’ve come over from English rule, have not seen the value and don’t want to upset the local politicians I think by ensuring that most schools should be integrated”.

WILLIAMS: “And yet for you it’s a no brainer”.

JILL HOUSTON: “Total no brainer”.

WILLIAMS: Integration is something happening in some unexpected places. In this Belfast commercial art gallery, two street mural artists are working side by side – that’s new. But what’s also unique is that they come from diametrically opposed backgrounds.

DANNY DEVANNY: “I’m just recreating a picture of Bobby. It’s a mural I did several….. well, many years ago on the Falls Road”.

WILLIAMS: This is Danny Devanny’s iconic mural of Bobby Sands, the IRA hunger striker who died in prison. Devanny’s artistic talents are well known in Republican areas. He was imprisoned for attempting to rob a bank to raise money for the IRA. Now he shares a gallery with Mark Irvine, the son of a Loyalist politician who was gaoled for fighting the IRA. It’s a level of collaboration unthinkable just a few years ago.

Danny Devanny hasn’t changed his political views. His work reflects a worldview of revolutionary struggle, but both he and Mark Irvine have bridged the religious and political divide. Their message, that with goodwill anyone can do it.

DANNY DEVANNY: [Mural artist] “We totally are appalled by the issues of sectarianism where young people are divided apart because of their religion. In fact the irony is, me and Mark live about a hundred yards from each other and we’d never met each other. His father would have been the same age as mine and in the end when we did meet we got on very well together. We have so much in common”.

WILLIAMS: “Do you worry it could descend back to the bad old days again?”

MARK IRVINE: [Mural artist] “You’ve always got that worry, but I can’t see sort of how that could happen. I think we’ve moved too far forward and I think that the general populous don’t want it. They just want to live a normal peaceful life and get on with their lives. I don’t think anybody wants to go back to the way it was”.

WILLIAMS: “Have you had any luck convincing him about the Unionist cause and vice versa?”

MARK IRVINE: “No. But we agree to disagree”.

WILLIAMS: Inside the glass and steel of a modern Belfast shopping mall, the dominant ideology is consumerism. It’s part of a new world where old brands seem unnecessary – Catholic, Protestant, Loyalist or Republican – and in the city streets and many residential areas, people do live peacefully side by side and yet it seems most in the city still see the removal of the walls a long way off.

FATHER TROY: “People still are fundamentally distrustful of each other and I think that’s why we have so many peace walls – “peace walls” in quotes - in Belfast. It’s bridges we need to build in this society and yet we’re very poor bridge builders. We’re actually brilliant here in Belfast at building walls”.

WILLIAMS: If ever a place was captive to its history then this is it. And yet there is real change. The camera-toting tourists are a clear sign of that. But the walls remain, and there’s not enough confidence to change that for now. Still, this was the only masked man we saw and with luck and goodwill, when he grows up, perhaps all of this will be gone.

MARTIN MCGUINNESS: “Those walls are obviously something that we would like to see removed and I think as the political process goes from strength to strength, that the day will come but I think that decision has to be in the hands of the people who live on both sides of the walls. Our job is to, within the political process, continue to make the gains that I know the vast majority of people welcome. Build a better future that our people want to see, and build a situation where people feel comfortable to remove those walls”.

WILLIAMS: In some areas the fires of sectarianism will continue to burn no matter what the politicians say. At this Loyalist bonfire, Republican flags and posters are destroyed. More often than not, nights like this use to end in violence. Not now. Perhaps the best that can be hoped for in these places is peaceful coexistence. Around here, that’s huge progress.

-

Edward Wechner's patents

My husband Edward Wechner's work - 2011 version....

-

Chainless Biycle

Edward 愛看Tour d' France, 每次看到看到那些賽手因為 jamming the chain, 而lose the race又或跌倒甚至傷得很重! 這是他自此而很大願望設計出一款比chain drive 鏈條單車更可reliability賴性, 更安全safety, without losing performance and without increasing the weight of the bicycle, but also inprove the efficiency...

-

Trench Casting Machine

It does dig a trench 300mm wide and 6000mm deep and fills it with concrete simultaneously at an advance rate of 20m/hour...

-

Us and Them, ABC Foreign Correspondent

300 多年前, 在 Northern Ireland, 大概有一大部份人是來自Ireland, 他們相信 Catholicism. 而剩下的另一大部份人是來自Scotland and England, 他們相信Protestantism 新教教會(應是Anglicans, 請看以下解說). 於是他們互相憎恨, 當然Catholics 都想趕走那些Protestants ..

-

Jesus Appears in a Toilet

Jesus Appears in a Toilet, Hahahahh! ...

-

The Link: Uncovering Our Earliest Ancestor? - 2

47 million year old fossilised remains. The most complete fossil proimate ever found. A missing link to the origins of man?....

TML'/

0 意見:

張貼留言